what is xlm trading at

What Stellar Lumens Teaches Us About Token Economics

![]()

Authors: Anshuman Mehta and Brian Koralewski

Introduction

Back in December 2017, we published a technical analysis of the Stellar protocol and its ambitions to become a cross-asset payment platform.

We lauded the breadth of Jed McCaleb and Stellar's vision of extending financial services and credit to the "unbanked."

Today, we reiterate our belief. These are challenges worth fighting for. Stellar's work is important, and it is required.

However, as investors, our primary focus is a dispassionate analysis of the economic model that underpins Stellar's investible asset — the Lumens token (XLM).

In our vie w , there must be a discernable economic link between increased network usage and returns to token holders.

We ask simple questions — How does the token generate returns? Is what's good for the network also good for the token?

Accordingly, we now analyze the XLM token model in context of Stellar's vision of developing a new financial system for the world. We unpack the sources of returns and determine whether these are attributable to token holders.

A complicated picture emerges.

Our Working Hypothesis

First, we acknowledge the basic regulatory and economic constraints within which financial services firms operate:

- Local and international laws and regulations in relation to financial services must be obeyed — if not immediately, then eventually and at a greater cost

- Prevailing regulations serve a real purpose — they safeguard customer deposits. Requiring depository institutions to issue risk-absorbing capital and submit to regulatory oversight are but a few.

- All digital money is information. The transmission of money is theoretically the non-replicable messaging of data. However, messaging is but a small part of complex money transmission business — other costs (e.g. KYC, AML, security) are extraneous and can be substantial.

- "Edge" use-cases are just that — edge cases. In order to have a meaningful impact, an upstart protocol must significantly upgrade existing infrastructure in major use cases (e.g. remittances to developing countries is c. 70% of global flow)

- There is substantial inertia to consumer behaviour when it comes to financial services. This is why multiple legacy incumbents exist and require considerable cost effort to displace.

- Stellar's target business segments — cross-asset payments and financial services — are heavily fragmented and extremely crowded with competing approaches.

- Consolidating market share is a far tougher proposition than consolidating technological expertise

The Lumens (XLM) Token Model

The Stellar protocol authorized c. 100 Billion XLM and issued 10.2B to the founding team and another 8B to the public, with a promise of more to come (via inflation and 'airdrops').

We asked a simple question — what are the sources of returns to an XLM investor?

We ignored returns solely attributable to XLM's price appreciation.

Capital gains without capital returns are merely a Ponzi-like redistribution of wealth. Eventually, an investment must generate returns to create value.

A distributed protocol must create sufficient utility to an external participant that they willingly purchase its token for some use case, adding an external of monetary value to an otherwise closed ecosystem.

We identified four such sources of revenues for the Stellar ecosystem — and concluded that not all of these accrued value to XLM holders.

- Operation Fees — write to the Stellar network's distributed database

- XLM as Medium of Exchange — Lend or sell Lumens as a 'step-through' currency

- Asset-pair Trading

- Commercialization of the Protocol

Revenue Source 1 — Operation Fees

The most obvious source of revenue is operation fees.

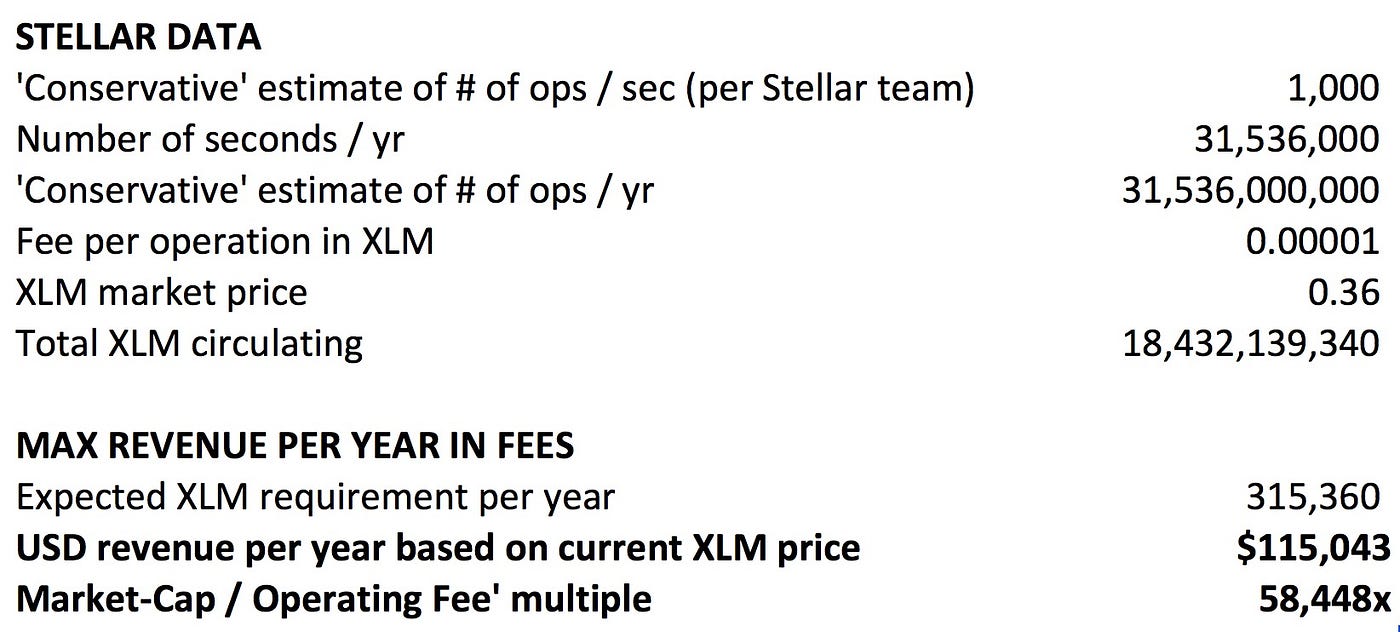

Perhaps in a nod to its Ripple-origins, Stellar prevents spam by instituting a hard-coded a fee of 0.00001XLM (100 "Stroops") per operation.

Equivalent to the transaction fees in Bitcoin blockchain or gas limit in Ether, this is price a user pays to commit their data to Stellar's distributed ledger.

(Note: we deliberately do not call Stellar's ledger a blockchain because the protocol is not a block-based system. Also note that an 'operation' is not to be confused with 'transaction' — a transaction may contain multiple operations.)

This hard limit, coupled with Stellar's own conservative throughput estimates of c. 1000 ops / sec, has the unintended consequence of limiting the total XLM required to run the network at peak capacity to only 315K XLM.

At a market price of $0.36 (as of Feb 8, 2018) this stream only contributes c. $115,000 revenue to token holders.

This makes intuitive sense — Stellar wishes to keep network near free to use to enable micropayments.

However, it does not bode well for Lumen holders.

And there is another dynamic at play here.

We consider this part of the business model most akin the incumbent SWIFT's messaging engine — the immutable transmission of instructions.

A member-owned entity, SWIFT generates c. $250m of earnings annually. Stellar aims to displace SWIFT. Startup wisdom dictates it must demonstrate a proverbial 10x improvement. This places a natural ceiling on the revenue potential from this stream.

Clearly, then, the operation fee is unlikely to be a significant contributor to XLM token holder returns.

Revenue Source 2 — Medium of Exchange

The second, and major use case of XLM is as a medium of exchange.

In order to full explore this aspect, we must first explore the part hard currencies play in global markets — as step-through currencies.

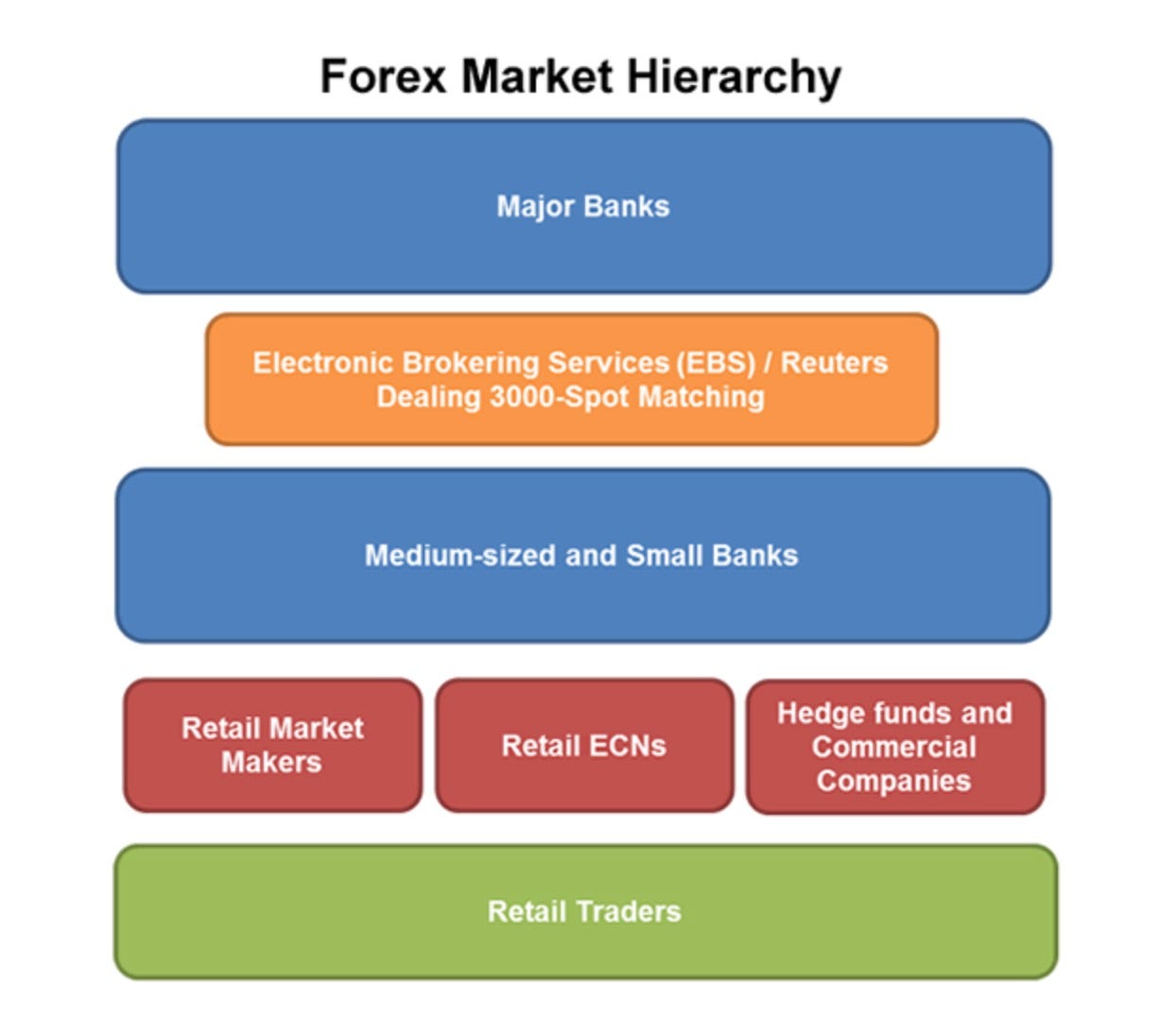

Let's consider the global FX market. The USD is the de facto reserve currency of the world, which means most other currencies trade against USD. The trading pair of a currency (e.g. GBP) and the USD tends to be the most liquid (highest flow) and frequently traded (smallest execution costs).

There are some notable exceptions (e.g. EUR/GBP is liquid and widely traded) but this principle largely holds.

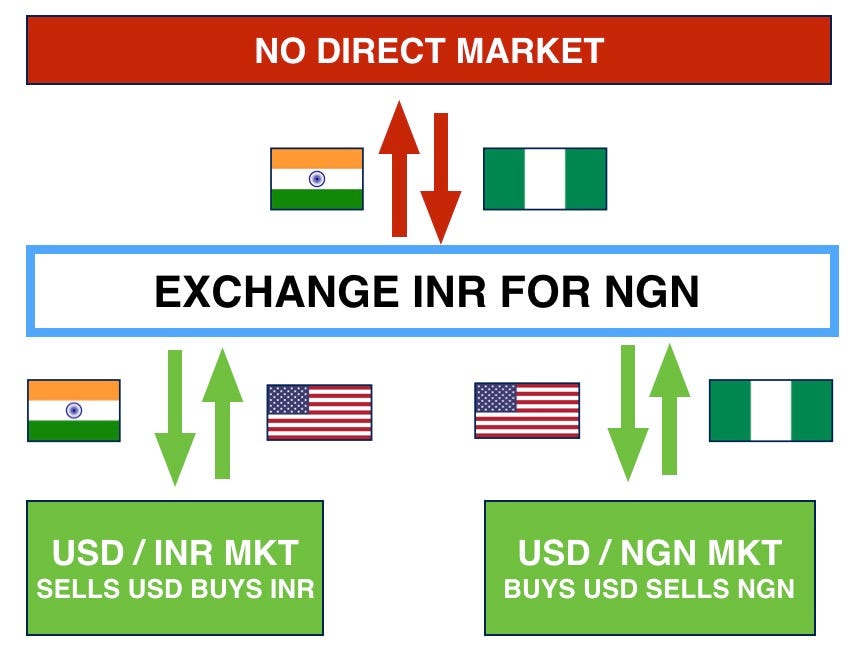

A corollary is that markets for smaller currency pairs (e.g. Indian Rupee — INR vs. Nigerian Naira — NGN) are illiquid and rarely trade direct.

If you want to exchange your INR for NGN, you'd have to sell INR, buy USD; then sell USD, buy NGN. This transaction would require two deep and liquid markets in requisite sizes — USD/INR and USD/NGN. If either market is illiquid, or closed, then either the transaction remains incomplete or someone in the chain takes on board outright FX risk.

Stepping through USD involves a trade-off between trading costs (legacy infrastructure, middlemen and regulations) and transaction reliability.

This realization takes us back to Stellar's original thesis.

We can send email immediately using digital protocols. All digital money is 0s and 1s. Shouldn't we be able to send money similarly?

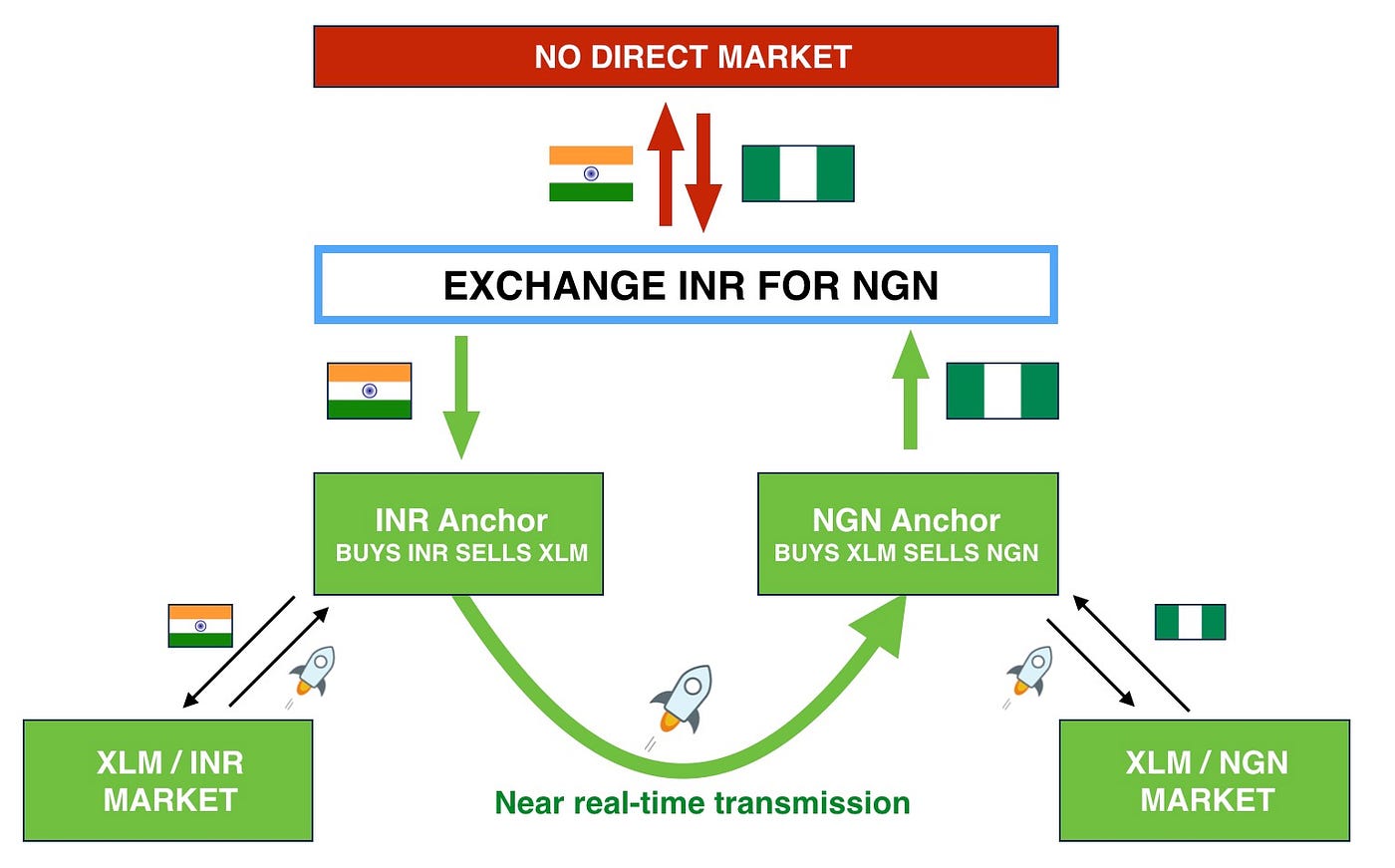

Stellar's answer is to introduce XLM — the step-through currency of the digital age.

Our NGN/INR transaction would trade thus –sell INR, buy XLM; sell XLM, buy NGN. We now need two deep and liquid XLM-XYZ markets (XLM/INR, XLM/NGN) and anchors with sufficient liquidity to process these back-to-back transactions.

Stellar's answer to one side of the liquidity question was to print XLM — lots and lots of it. XLM was originally 'free' to print, as it emanated from code, and the authorized token base of 100B+ had no discernable grounding in science.

To create the other half of a liquid market, Stellar plans to on-board anchors that have natural INR and NGN liquidity (Indian and Nigerian banks) and allocate them as many free XLMs as required to 'seed' the market.

Further, anchors that end up with bought (or sold) residual XLM positions should be able to offset these immediately.

Arguably, no one outside the Stellar universe has any need for XLM. We live in a fiat currency world, and likely won't be using XLM to pay electricity bills or buy milk any time soon.

Thus, the Stellar protocol allows all external participants to interact with each other in an effectively XLM-free manner through the introduction of Atomic or boolean "all or nothing" transactions.

To go back to our INR/NGN transaction — it will be concluded the instant XLM/INR and XLM/NGN anchors line up at the same time, at the right price and the right size.

There are exceptions, of course — an anchor may choose to run an XLM portfolio for profit or speculation. But we believe this will be a small fraction of the overall flow.

Now, in the real world, transactions are settled on a net-settled basis. FX dealers run trading books in a currency of their choice and lay off net risk in institutional markets. The process works up the chain till you reach the large international clearing banks that handle global flows on an aggregate basis.

In an XLM world, this institutional market will need to be created, and, because we live in a fiat currency world, this will be in 'addition to' rather than 'instead of' existing institutional FX markets.

So how does a token-holder make money in this schema?

To align the INR/XLM and XLM/NGN trades above, the protocol will require, for a brief period, an adequate supply of XLM. For 4.5 seconds to be precise, which is the time required to settle a transaction.

Purchasing or leasing XLM from holders, perhaps for a small fee, can fulfill this temporary requirement for XLM. Banks run similar businesses in their Equities Finance and Repo desks. The economics are well understood and subject to market dynamics.

In theory, anchors purchasing XLM from the public to maintain trading reserves would represent an excellent source of revenue to token holders.

However, we note that the Stellar Whitepaper provisions for airdrops to anchors. It is not clear if these airdrops will suffice for the anchor's requirements, thereby eliminating any market transaction in XLM.

This presents a substantial risk to token returns.

Revenue Stream 3 — Asset Pair Trading

Each leg of an asset-pair transaction (e.g. INR/XLM and XLM/NGN in our example) will require market makers — anchors that take the opposite side of each trade leg.

In the FX world, these are usually entities that have a natural position in that currency (e.g. Indian or Nigerian banks or corporates).

Such market making activities are a well-established business model across traded markets. Dealers generally make markets for a small bid / offer margins — i.e. the difference between buy and sell prices.

Similarly, we expect Stellar anchors to take small margins for this service.

The revenue thus earned is attributable to trading operations, not to public XLM holders.

FX Dealer (and likely the Stellar anchors) set bid/offer margins independently. We do not expect Stellar to dictate these margins and nor be able to control this aspect of end-user pricing.

What if atomic swaps do not perfectly align?

For example, the Indian market may be closed when an INR/USD or INR/XLM request is received.

In real-world FX market, a dealer could choose to fill the customer order but leave his own book imperfectly hedged. The dealer would trade conservatively (i.e. factor in a bigger margin) to cover for unexpected price movements.

The Stellar white paper does not suggest that anchors have this option.

Even if they did, the incremental revenue earned from running un-hedged XLM risk would still belong to the anchors and not token holders.

Revenue Stream 4 — Commercializing Stellar protocol

In 2017, the Stellar Foundation assigned some core team members to Lightyear (www.lightyear.io).

The Stellar — Lightyear relationship is based on the Linux Foundation — Red Hat model.

Lightyear will be tasked with commercializing the Stellar protocol — generating revenue through consulting, customization, implementation and maintenance contracts from its enterprise clients.

In an oblique sense, Lightyear's success may lead to increased demand for XLM tokens subject to the constraints described in Revenue Streams 1, 2 and 3 above.

However, whilst Lightyear's business activities represent significant revenue potential, this revenue will be attributable to Lightyear's own corporate structure, it's employees and common stock shareholders.

None of this revenue will funnel back to XLM holders.

Explaining XLM's Multi-Billion 'Market Cap'

Stellar will eventually issue 100B+ Billion tokens. At a current market price of ~$0.36 per token, that suggests the market expects a total 'market cap' of almost $35B+.

Our investigations thus far have not come close to how XLM holders may accrue such riches.

So, what gives?

We believe the market is pricing in another dynamic — an assumed and inexorable transformation of XLM from medium of exchange to a store of value.

To examine further, we must go back to a hypothesis first circulated in 2015.

The proponents assumed that Bitcoin network would be used for the global remittance trade and capture 10% of the market share. The global remittance volume was $450B at the time. This gave a remittance market share of $45B.

The author(s) then surmised that in order to transmit $45B, one would need to purchase $45B of Bitcoins. Based on the then issuance volume of 14M Bitcoins, this yielded a price target of $450B / 14M = $3,000 per BTC.

Similarly, some XLM holders believe that issued volume of XLM will rise in price to become equal to the transaction value the protocol is transmitting. The annual remittance market is now $550B+. Adding an even larger non-remittance addressable market, speculators believe 100B of authorized XLM will go "to the moon".

As a result, XLM's traded at a high of $0.85 per XLM in early January of 2018.

We believe this is a deeply flawed analysis.

Let's unpack this claim further.

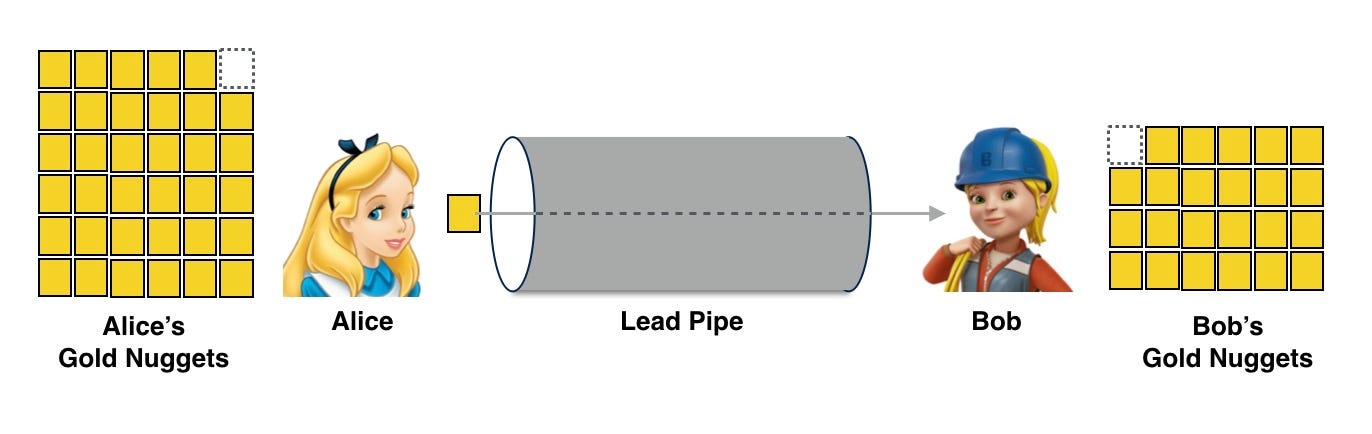

Alice, Bob and a Lead Pipe

Meet our friends Alice and Bob.

Alice needs to give Bob a gold nugget. She can wrap the nugget in wrapping paper and hand it directly to Bob. Bob unwraps the paper and discards it.

In this scenario, the gold nugget is still worth $1 Billion. The transmission mechanism i.e. the wrapping paper is worthless.

Or Alice can also use another transmission mechanism — say a lead pipe — to keep the gold away from prying eyes. She inserts the gold into the pipe and slides it across to Bob.

For a few seconds, as the gold travels through the pipe, the pipe is worth a billion dollars. Once the gold reaches the other end, and Bob removes safely removes it and the pipe reverts to being just that — an empty lead pipe.

The lead pipe merely serves merely as the conduit. The gold nugget does not belong inside the lead pipe, nor does it belong to the owners of the pipe. (Unless, of course, the pipe owner blocks one end of the pipe and makes off with the gold. And that's plain illegal.)

Not so in the aforementioned Bitcoin analysis.

The analysis assumed that because the Bitcoin network would carry $45B of remittances per year, the value of the Bitcoin network would become $45B.

Even before we point out that the remittance volume is an annualized figure and token prices are measured at a particular point in time, or that this analysis ignores token velocity, this logic is plain wrong.

The authors confused the "medium" for the "message", the agents for the principals.

Transmitting $45bn doesn't make the transmission mechanism worth $45bn, no more than placing a gold nugget in a lead pipe makes the lead pipe worth the price of gold.

The remittances channeling through a protocol belong to the remitters and the receivers, not to the protocol or the token holders.

To the latter belongs only the remittance fee — the price Alice is willing to pay for the safe transmission of the gold. And this is a small fraction of the cost of the gold nugget.

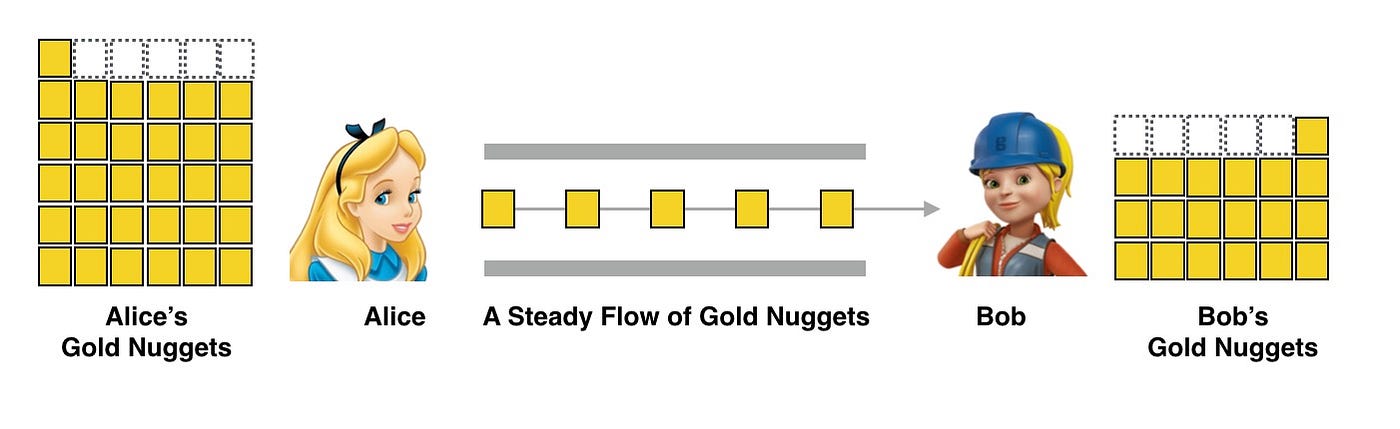

A Constant Flow of Gold Nuggets

Ah, you say, but no transmission mechanism conducts only one transaction at a time. Surely, a network that transmits $45B of remittances per year has $45B of value locked in?

To examine this point, let's extend our Lead Pipe analogy a bit further.

Let's assume that Alice sends 31.5M nuggets per year — quite an impressive volume. Is the lead pipe now worth the total volume of nuggets (31.5M) it transmits?

Not quite.

31.5M nuggets a year still only equates to a gold nugget each second. As our lead pipe is as efficient as the Stellar protocol, each nugget only takes 5 seconds on average to 'settle' i.e. reach Bob.

And Bob promptly removes the nugget from the pipe upon receipt.

This means even with a high annual volume (31.5M nuggets), the lead pipe only has 5 gold nuggets travelling through it at any given moment.

This is an important conclusion.

By this measure, even if the now global remittance business of $550bn moves to Stellar, the network would only hold c. $75k of value at any time ($15K / sec * 5-second 'operation' settlement period, assuming a steady flow of remittances.)

This is great for the network but lousy for the token. Why? Because this implies that we need a far lower volume of tokens to support a network than the 100B XLM.

The actual answer will depend on token price, velocity and circulation friction. A functional system that efficiently recycles tokens will drive token utilization down to the minimum required.

Over-issuance of this magnitude has significant consequences for token price.

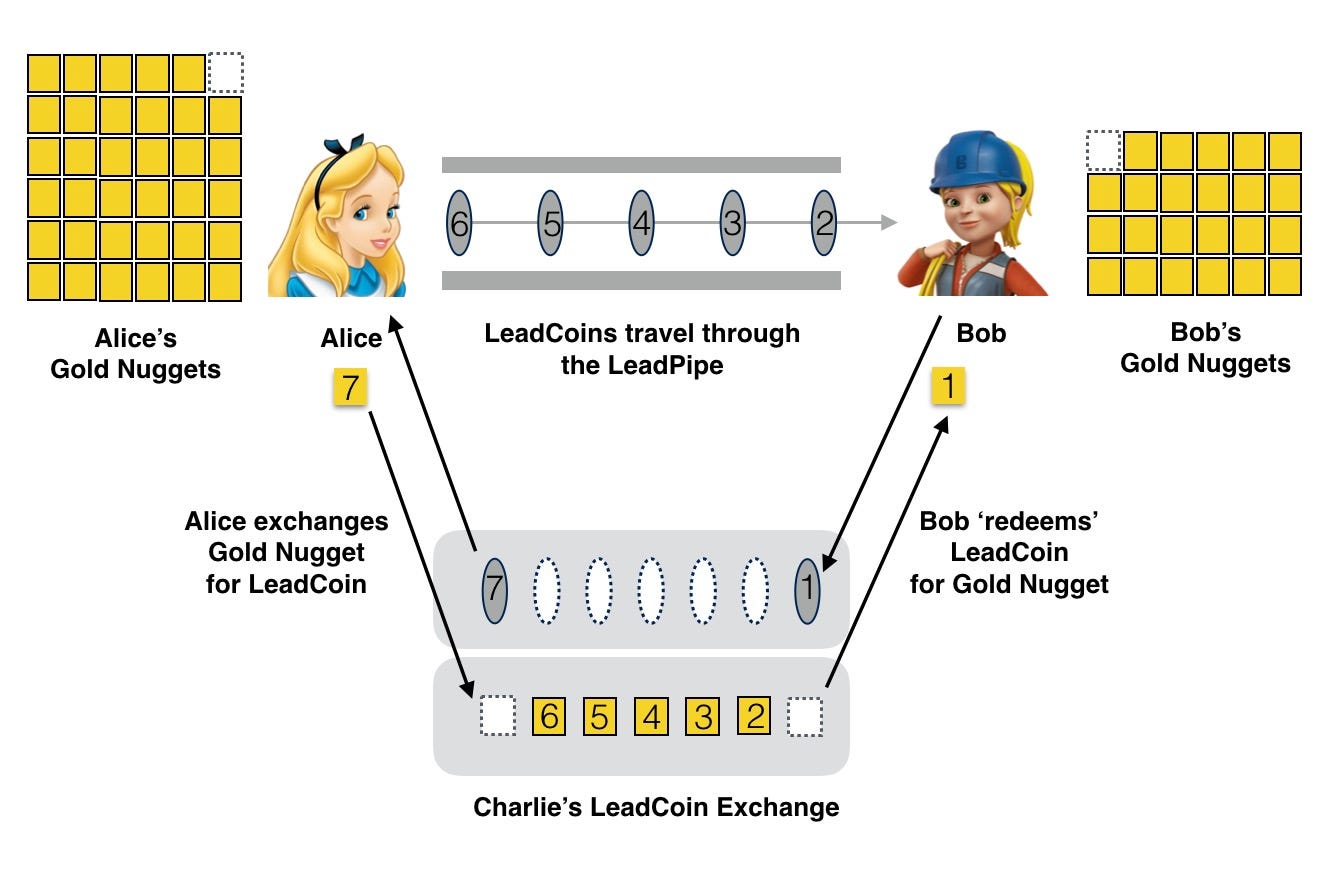

The LeadCoins Obfuscation

Our analogy is great for understanding the divide between the principal (or the owner of value) and the Agent (or the transmitter of value).

Remittances (gold nuggets) are not the channel (lead pipe). Remittance beneficiaries (Alice and Bob) are not XLM holders (lead pipe owner).

The analogy is also imperfect.

In crypto-currency implementations, distinctions can become blurred. In order to remit money through the Bitcoin network, one must purchase Bitcoins. To use Stellar, XLM and so on.

A closer approximation then is if Alice needs to convert her gold nuggets to a crypto-currency, let's call it LeadCoins, minted and controlled by Charlie who owns the lead pipe.

So how does our analysis evolve? We call it The LeadCoin Obfuscation.

In this scenario, Alice trades her gold nuggets for LeadCoins and transmits them to Bob. She willingly pays a small fee for the transmission of gold.

At the other end, Bob receives LeadCoins and exchanges them for gold nuggets.

As before, neither Alice nor Bob have any off-pipe use for LeadCoin. Bob immediately exchanges the LeadCoins for gold nuggets.

One could argue that the act of buying a gold nugget 'worth' of LeadCoins would cause one LeadCoin to rise in value. And to the extent Bob leaves LeadCoins in the pipe, whether for speculation or future use, the value of the pipe may rise by the equivalent of gold nuggets not redeemed. In the short term, these relationships probably hold.

But the underlying economics are unmistakable.

Alice and Bob are in the gold business, not the LeadCoin business. So long as they are able to purchase and sell LeadCoins for the purpose of transferring their gold, at predictable prices and in the right amount, the LeadCoins may as well not exist for them.

Similarly, the global remittance business accomplishes a transfer of fiat money for end-user requirements, not to build crypto-currency positions or inflate token prices.

When evaluating the intrinsic value of a payment network token, what matters is how much revenue Charlie is able to collect from Alice for the use of his LeadCoins. Printing 1B, 10B or 100B LeadCoins only serves to dilute the per-coin 'share' of revenues that is attributable to each token.

An increase in network value caused by high token issuance volume is short-lived and unsustainable.

As someone once said, mo' tokens, mo' problems.

Debunking the Network Value to Transaction (NVT) Ratio

The Lead Pipe Analogy also debunks the so-called Network Value to Transactions valuation — or NVT ratio — for payment protocols (such as XLM and even Bitcoin).

When scrutinizing utility-token platforms, where a native token is required to utilize the network, the NVT is a good indicator of platform activity, but arguably not the end-all in valuation metrics.

Payment platforms (utilizing XLM-like "step-through" currencies), decentralized exchanges (i.e. 0x) and certain scaling solutions that require a native token (such as the Raiden Network) require high token velocity to function efficiently.

An increase in transactions is undoubtedly positive for the protocol. However, the ratio of Network Value to Transactions, which really is the measure of transaction volume transmitted across the network, pertains to the senders and the receivers (e.g. the anchors and asset issuers in Stellar-speak) and not token holders who merely enable this transmission.

Therefore, no meaningful conclusions about intrinsic value of the tokens can or should be drawn from the ratio of Network Value to Transactions.

Even store of value or digital gold use cases (as Bitcoin's other main function is believed to be) should not be evaluated according to the NVT ratio, as hodl-ing artificially inflates the overall metric.

A piece on scrutinizing the current Crypto Valuation methodologies such as the highly touted MV, PQ equation will be released in the coming weeks. Ask to be notified here.

Revenue Sources — Our Conclusion

So we conclude that in the case of asset transmission protocols, whether Bitcoin, Stellar or any other, the total value attributable to the owners of the network is a combination of revenue sources described in Revenue Streams 1 to 4.

The network never becomes that which it is transmitting.

And by the measure of token design, XLM substantially falls short of revenue expectations.

Stellar — Further Challenges

Stellar has set out to address two major challenges facing developing nations –

- access to financial services (or banking the underbanked); and

- helping small businesses thrive through access to credit

We examine the challenges ahead in achieving these goals.

Banking The Under-Banked

In our view, banking the under-banked goes beyond smartphones and XLM-only wallets.

Our base assumption here is that the under-banked will continue to live in a "fiat world". An XLM-only wallet, whilst technologically feasible, will remain impractical for daily use unless linked to a fiat-currency bank account.

Furthermore, providing fiat bank accounts to the under-banked is only in part a technological challenge for the existing banking infrastructure.

The rest is economic — meaning the economic rationale behind serving the low-income and low-wealth segments. Remote, hard to reach or uneconomical-to-serve segments still need to be accessed, provided with documentation identity and a means of accessing wallets offline or online (physical branches or network connectivity and smart phones).

This is a tough ask, and the answer is broader than 'better technology'.

We do not expect the Stellar Foundation's enablement of financial services to extend to the recreation of financial services infrastructure from scratch. These undertakings harbor significant costs and we do not believe the Stellar Foundation or Lightyear have the wherewithal to undertake these on their own.

Instead, we welcome their proposed partnerships with local banks and money service agents.

But we note that partner cost structures and profit margins will likely remain beyond Stellar's control.

Enabling Access to Capital

Stellar's second key focus is enabling access to credit for under-served borrowers globally.

In the most simplistic, and most likely scenario, local clients meet their financing requirements in local currencies. E.g. Nigerian businesses borrow in the Naira from Nigerian banks and generate Naira-denominated revenues.

We are not clear on what role Stellar would play in this local-to-local transmission.

Would this be as payment gateway between local finance companies and local borrowers? Or would Stellar providing an immutable credit score to borrowers by recording history of borrowings and repayments?

Enabling Cross-Border Investments

Cross-border provision of credit is rare and, in the case of most emerging countries, complicated by capital controls in place on foreign investments.

It also introduces FX risk, which must be borne either by the lender or the borrower.

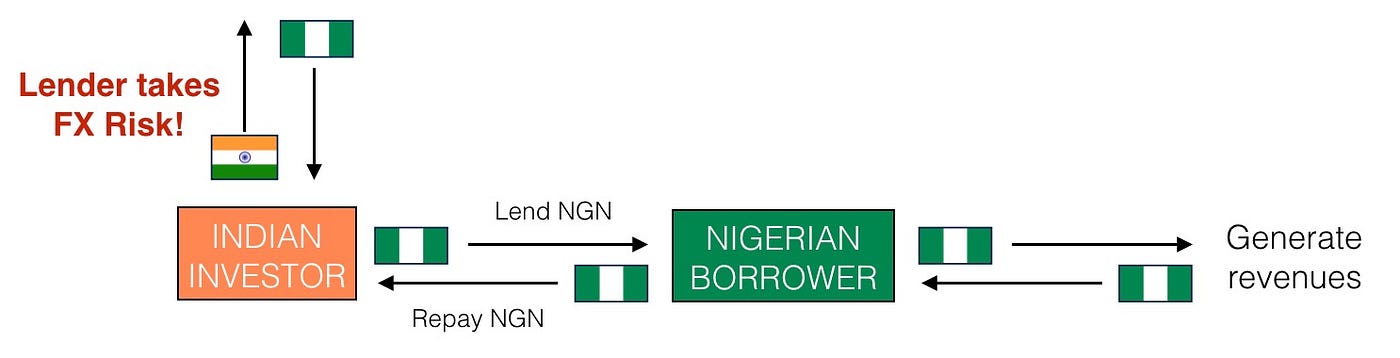

Let's take an example of an Indian investor lending to a Nigerian small business through the XLM network.

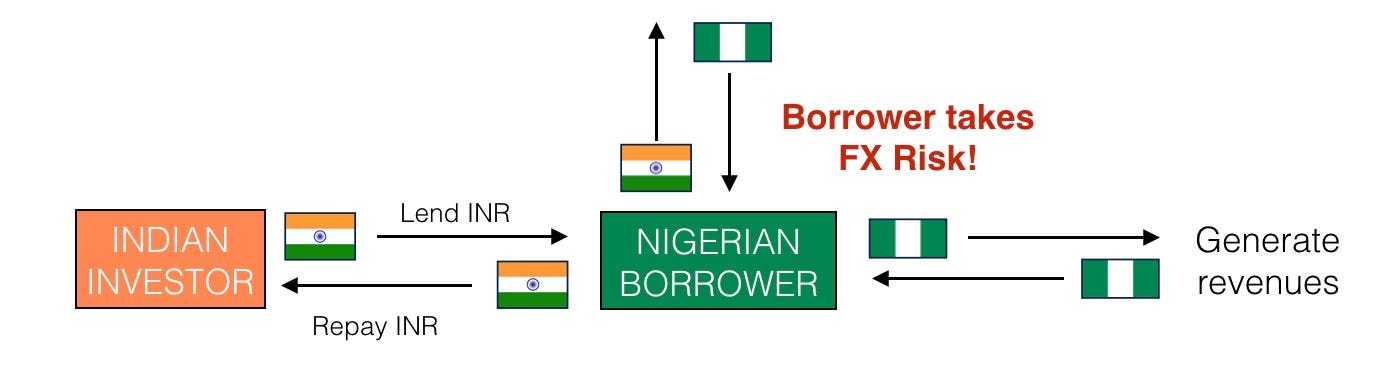

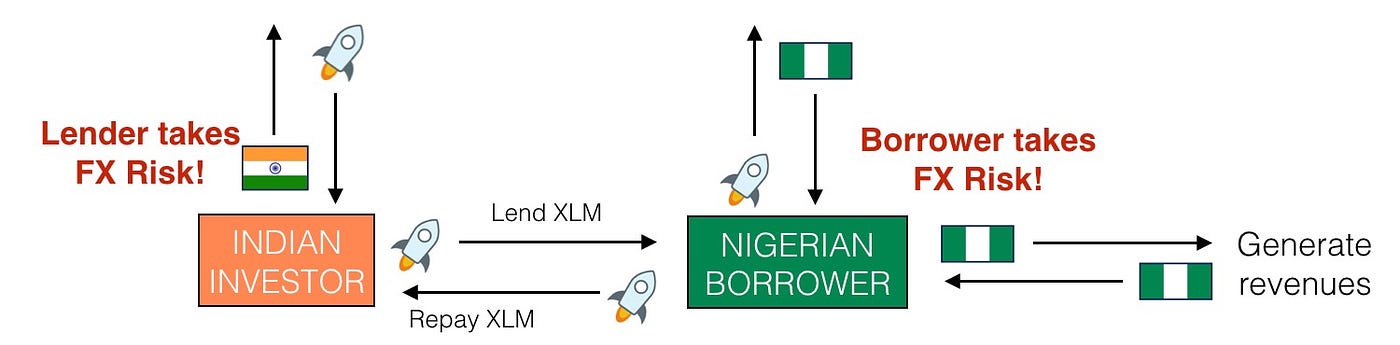

In this scenario, who bears the FX risk is determined by the currency in which the borrowing is denominated.

If the borrowing takes place in NGN, then the Indian investor bears INR/NGN FX risk. A depreciation of NGN against INR means the investor recoups less of his investment, when the borrower repays the same NGN amount.

If the investment is denominated in INR, then the tables turn — now it is the borrower who suffers if the NGN weakens. The borrower needs to conjure up more NGN to repay the same INR.

Finally, some crypto lending platforms attempt to lend in the native crypto-currency or token. If the lending takes place in XLM, then both sides are exposed to FX risk. This risk does not offset, as XLM may be affected by other factors (e.g. Bitcoin price), introducing something called basis risk into the equation.

We note that in all these scenarios, the borrower still needs a bank account or relationship with an existing money service business to actually receive physical NGN. Tech innovation has not supplanted the real world yet.

One Last Thing — How Many XLM are Enough?

The release of the authorized but as yet un-issued XLM tokens (c. 87B per the Stellar Foundation) will further dilute the revenue potential of XLM holders.

The relationship between the 100B Lumens, token price and frequency of usage isn't clearly understood nor established by precedent.

We have already calculated that only 350K XLM tokens are required for full-capacity operation fees. If token velocity is high then even a small token volume could theoretically provide step-through function for the entire network.

Additionally, atomic swaps may further reduce the incentive to hold large XLM reserves thereby depressing price potential.

The ecosystem simply may not have enough demand to utilize all the 100B+ tokens, even at full steam.

Conclusion

Stellar is an extremely powerful application of distributed ledger tech. We greatly admire Professor David Mazieres' innovative work in developing the consensus protocol, and greatly commend the efforts of Jed McCaleb and the Stellar team in bringing his work to life.

However, we also believe that the intrinsic value of an XLM token is called into question on purely economic terms.

- A hard cap of 0.00001 XLM 'write' fee per operation

- Airdropping XLM required for atomic swaps to anchors

- Protocol efficiency with high token velocity and future dilution

- External revenues generated in trading XLM / Asset Pairs

- External Lightyear revenues from commercializing protocol

- Real world barriers to "Banking the Unbanked"

- A lack of pricing power over end-user pricing

Stellar's design decisions bring into sharp focus the importance of good token governance in a distributed context.

The Lead Pipe analogy is merely the first in a series of frameworks that we will publish in the coming weeks. Our mission is to foster the creation of token design best practices and the issuance of high-benchmark tokens in any distributed context.

We believe this work is imperative if the distributed ledger ecosystem is to thrive.

To request our token design frameworks, or read more of our past research, contact us here.

Source: https://medium.com/@anshumanmehta/what-stellar-lumens-teaches-us-about-token-economics-80e3ac14aa71

Post a Comment